As most medical professionals know, HIPAA gives individuals rights over their health information, and it sets limits on who can look at and receive medical data. But HIPAA extends beyond documents at the doctor’s office, and when it comes to the law’s girth, breadth and bite, the hippo is an apt comparison.

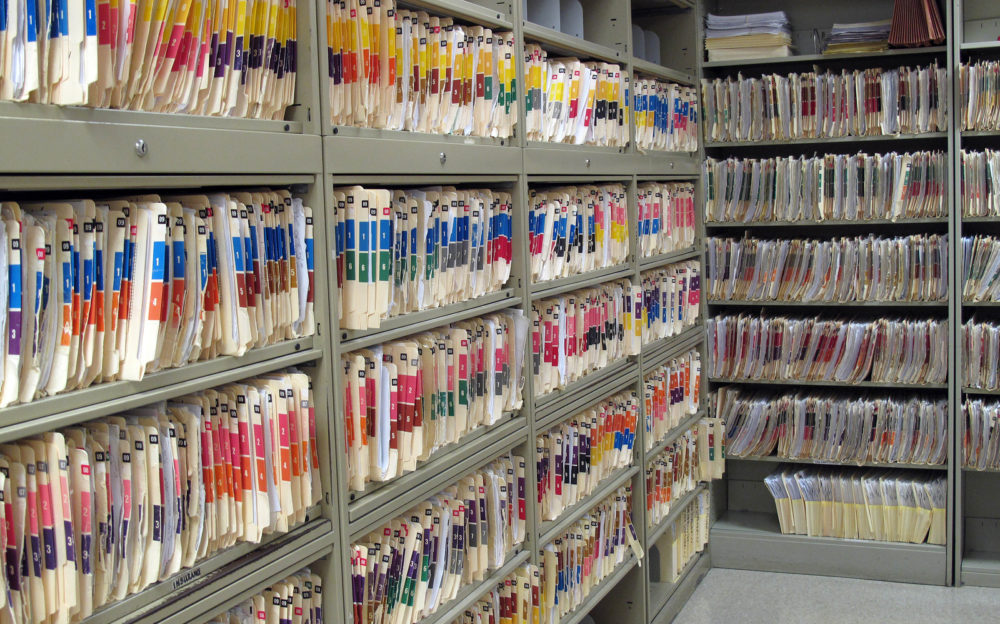

The HIPAA Privacy Rule applies to all forms of so-called protected health information, whether electronic, written or oral. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 41 percent of Americans have never even seen their health records, yet 80 percent of people who have viewed their medical files find it valuable. Society places a value on these records for both personal and financial reasons, and of course, we don’t want the world to know our medical histories.

The stories of HIPAA enforcement are legend: the HHS website is intentionally replete with enforcement cases to warn the world about non-compliance. As a hippo protects its calf, HIPAA is often used to chase down violators in the name of privacy rights.

For example, recently HHS’ Office of Civil Rights, the office that investigates HIPAA complaints, reached a $2.2 million settlement with a New York hospital for the disclosure of two patients’ protected health information to film crews and staff during the filming of “NY Med,” an ABC television series, without first obtaining authorization from the patients. Investigators found that the hospital allowed the ABC crew to film someone who was dying and another person in significant distress, even after a medical professional urged the crew to stop.

In another case, a Los Angeles physical therapy practice agreed to pay a $25,000 HIPAA violation fee for disclosing numerous individuals’ protected health information, when it posted patient testimonials, including names and images, to its website without obtaining valid, HIPAA-compliant authorizations.

“Recently HHS’ Office of Civil Rights, reached a $2.2 million settlement with a New York hospital for the disclosure of two patients’ protected health information to film crews and staff during the filming of ‘NY Med,’ an ABC television series”

These examples probably speak to issues most medical practitioners might recognize as problematic. But HIPAA goes beyond this, particularly as expanded by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, or HITECH. Here are five HIPAA recommendations that you may not be aware of but need to know:

HIPAA in the Workplace: If an employer handles patient information in any way, that business is bound to comply with HIPAA in the workplace as well, particularly when dealing with health insurance plans, health spending accounts, wellness programs, adhering to the Family Medical Leave Act or worker’s compensation. Human resources employees should be properly trained on HIPPA laws or your company and HR employees could be targeted in a lawsuit. For instance, supervisors can ask for doctor’s notes from employees, but they are not allowed to ask health care providers for medical information without the employee’s consent, which must be properly documented. As a result, non-medical businesses in receipt of patient data, such as law firms handling injuries, divorce and disability, must similarly take steps to protect that data much like a physician or hospital should.

HIPAA in the College Setting: Even though many parents foot the bill for their college-age children, that investment doesn’t guarantee the right to your child’s medical information at a college clinic; remember, they’re adults now, as they’ve probably told you repeatedly. Parents may want to obtain HIPAA authorizations that give your child’s doctor’s permission to discuss their medical situation with trusted family members who have been specifically authorized. These documents are inexpensive but priceless in a pinch. In medical emergencies, college administrators may contact parents in spite of The Privacy Rule, but this could cause potential legal problems for the college if the student is not on good terms with their parents.

“According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 41 percent of Americans have never even seen their health records, yet 80 percent of people who have viewed their medical files find it valuable”

Sharing Medical Information: Medical practitioners need to understand that texting staff or a colleague with questions/answers about patient care or a shared patient may be problematic; there is no way to assure safe viewing and transmission of the data. While there is no one-size- fits-all solution for fast workplace communication, as a general rule, practitioners need to have a secure system in place such as a third party messaging service with encryption, along with an office policy for such messaging. HIPAA and HITECH also requires vendors and business associates, such as medical bill collectors, to have certain electronic safeguards in place when transmitting medical information, something that many practices are deficient on. Once medical files are tendered to a patient, the medical provider is no longer responsible for the security of that information, but it may be wise to include a disclaimer to this effect with released records.

HIPAA and Firearms: On January 4th, 2016, HHS permitted certain covered entities to disclose to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System the identities of those individuals who, for mental health reasons, are prohibited by federal law from having a firearm. The information that can be disclosed is the minimum necessary identifying information about individuals who have been involuntarily committed to a mental institution, or otherwise have been determined by a lawful authority to be a danger to themselves or others. The new modification is narrowly tailored to preserve the patient-provider relationship and ensure that individuals are not discouraged from seeking voluntary treatment.

Court Orders and State Agencies: A HIPAA-covered healthcare provider or health plan may share protected health information if it has a court order. However, the provider or plan may only disclose the information specifically described in the order. The Privacy Rule permits healthcare providers to disclose protected health information, without authorization, to public health authorities, who are legally authorized to receive such reports for the purpose of preventing or controlling disease, injury or disability. This would include, for example, the reporting of a disease or injury; reporting vital events, such as births or deaths; and conducting public health surveillance, investigations or interventions. If a provider receives a court order for medical data, they can only disclose what is legally required. If questions arise, contact legal counsel to determine the scope of the request before responding.

As you would with a hippo in the wild, err on the side of caution when handling protected health information. Make use of available resources to train staff about HIPAA compliance and make sure those who do business with you have their own policies in place for compliance. To learn more about the act, visit www.hhs.gov/hipaa.

Recent Comments